MORAB ARTICLES

A History &

Information service of the Box LT Ranch

Creating, producing and distribution of Morab media

Click for articles

HISTORY OF THE MORAB

Morab Horse Breeding In The 2000's

ARABIANS IN THE MORAB

…

WHERE WE CAME FROM

Morab Historian Ted W. Luedke, Ava, MO, March 2005

W.R. Brown’s Maynesboro Arabian Stud

There are a handful of early Arabian breeders in the

USA that we can say were the reason the Arabian came here and began to prosper. I have worked with historians from both parent

breeds and most recently with one from the Arabians who is working on a book about the

famed Arabian breeder, W.R. Brown. She

offered to include Morab connections so I provided her the research and decided to do this

article.

Randolph Huntington,

who saw in the Arabian stallions Leopard* and Linden Tree*, the opportunity to found a

national horse for the United States. Huntingtons

Americo-Arab project, based on President Grants stallion’s and mares by the trotting

horse Henry Clay, disappeared rather quickly. He did found a more lasting tradition when

he imported the Old English (non-Crabbet) Arabian mare *Naomi and sent her to *Leopard.

The resulting 1890 foal, Anazeh, was the first Arabian bred in North America to leave

registered descent.

J.A.P. Ramsdell bred Arabians for only a few years, but appears

to have made an effort to collect the best stock available. His effective foundation mare

was the best of the Hamidie mares, *NEJDME.

Her descendants are prominent in modern pedigrees. Ramsdells sires were the Ali Pasha

Sherif stallion *SHAHWAN, imported from Crabbet; *Garaveen, bought from Huntington; and

Davenports famous Crabbet stallion *Abu Zeyed.

Homer Davenport is responsible for the single largest contribution to

the uniqueness of American Arabian breeding. At least 20 of his 27 desert imports have

bred on into modern pedigrees. The Davenports represented an unusually broad cross section

of the desert stock, for the tribes were in summer quarters at the time of his journey and

he was able to contact more of them in the time available.

*Hamrah and *Deyr became the most influential of the Davenport sires, while

there are too many healthy Davenport female lines to list; *Wadduda and *Urfah are

particularly influential.

W.K. Kellogg’s California stud at Pomona was another major breeding

ground. Located diagonally across the

continent from New England, Kellogg began with horses of Davenport breeding. His stud played the same role in terms of

that group as Browns did with the Borden, Huntington and Ramsdell stock: much of the

Davenport influence in modern Arabian breeding is there because Kellogg bought horses of

this breeding; using some and selling others. Arabians

from other sources, including the Draper Spanish import *Nakkla and the Tahawia mare

*Malouma, bred in Egypt from desert parents, became important members of the Kellogg

program.

Now that brings us to two of the most prominent and

some would say important of the time, WR Brown and Spencer Borden. The Brown stud was the successor to Bordens as

what turnes out to be the premier Crabbet nursery in North America. To look at Maynesboro we then must first look at

Interlachen.

Spencer Bordens’

Interlachen Stud was the premier North American Arabian nursery in its day.

He imported horses from the Blunts and from other English breeders; his most important

individuals were the great mares *Rose Of Sharon, a major producer at the Blunts Crabbet

Stud and dam for Borden of *Rodan and Rosa Rugosa; and *Ghazala, bred by Ali Pasha Sherif,

dam of Guemura and Gulnare. These are still quality Arabian breeding programs today.

W.R. Browns’

Maynesboro Stud was the successor to Soencer. The Crabbet and Old English heritage of the

Borden, Ramsdell and Huntington stock would not be represented as strongly as it is in

modern breeding were it not for Browns use of those lines at Maynesboro. Earlier Crabbet

imports of *Rodan, *Abu Zeyd and *Astraled were joined by Browns own imports from Crabbet

which included the great sire *Berk and at least nine mares destined to found influential

families. Wilfrid Blunt, shortly after his

wife's death, systematically sold off her most prized animals or their surviving

offspring; many of the horses favorably referred to by Lady Anne in her journals are

closely represented in Maynesboro pedigrees.

The Maynesboro Arabians represent the strongest

surviving sources of many of the most esteemed early Crabbet lines, lines which in some

cases are lost, or nearly so, from modern English breeding. Gulastra, Ghazi, Rehal,

and Rahas were just a few of the major sires bred at Maynesboro. The mare line founders

include Ghazawi, Ghanigat, Bazrah, Rabiyat, Ghazayat, Raad, Bahreyn and Nusara.

Maynesboro was a farm where Arabians were used for

family riding and worked in light harness, and most visibly, took part in the U.S. Mounted

Service Competitions, better known as the Army endurance rides. Both Borden and Brown had

worked to get the Arab recognized as the natural horse for the U.S. Cavalry. Even though

Brown’s horses retired the Mounted Service Cup by winning three of the Army rides,

there were not enough Arabs to mount the Cavalry. The U.S. Remount did accept the Arab as

worth standing to grade mares to breed potential cavalry mounts.

Brown also imported Arabians from France and Egypt.

The Maynesboro French influence survives most strongly today through the mares Follyat and

Fath. The former is ancestress of Muhuli, Aurab and Kontiki, while the latter produced

Alyf and was granddam of the Selby matriarch Woengran. The Brown Egyptians are still

widely influential, including such familiar names as *Nasr, *Zzrife, *Roda, *Aziza, and

*HH Mohammed Alis Hamida.

Maynesboro horses also played a prominent role at the

Kellogg establishment. The Browns mares produced some of the best of the Kellogg stock.

Rabiyas (Gulastra), the last foal bred by W.R. Brown, was for years the Kellogg head sire,

numbering among his offspring the horse probably most readily associated today with the

Kellogg name, the great endurance sire Abu Farwa.

The Arabian Data Source shows that Brown bred and registered 194 Arabians. Of those, we find 22 that have bred on such that we find them in the pedigrees of Morabs registered in the International Morab Registry. Of the 22 some are off spring of others leading us through Intricate, interconnecting pathways, bringing the number down to 7 beginning individuals. These seven listed below represent 242 Morabs, with not all but what the author feels are their Significant Down Line, and those are not in pedigree order.

Azkar AHR1109 1 Morab

Significant Down Line: Aalzar AHR7984; Aazrar AHR10429; Izkar AHR8424 and Kazal AHR12344.

(No photo available)

Bazikh AHR0618 1 Morab

Significant Down Line: Tahir AHR2413

(No Photo Available)

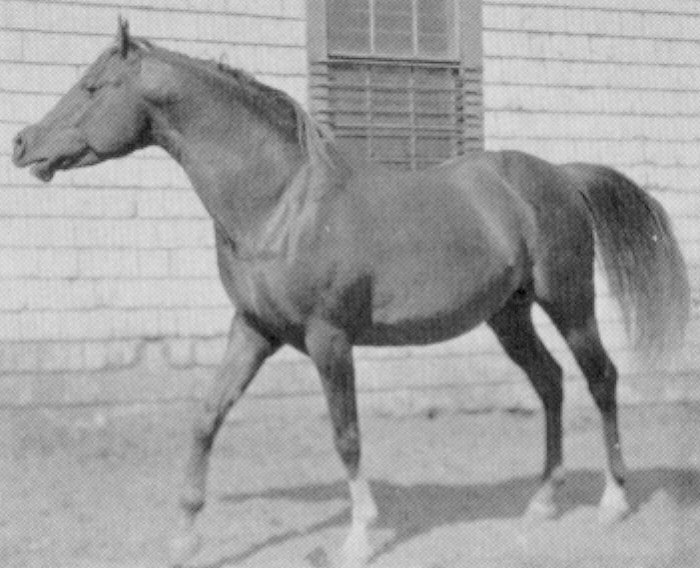

Ghazi

AHR0560 140 Morab

Significant Down Line:

Antonia AHR1596: Ankara AHR5161; Daufin AHR10473; Gabilan AHR4405.

Ghazawi: AHR0802: Aurab AHR12488; Fadjur AHR7668; Fadi AHR16761; Ferzon AHR7723;

Gay-Rose AHR11891; Gazon AHR9875; Khemosabi AHR45471; Raffon AHR19040 and The Real McCoy AHR17362.

Narzigh AHR1745: Aurab AHR12488

Gulastra AHR0521 59

Significant Down Line:

Islam AHR1709;

Katar AHR0724;

Rahas AHR0651; Almiki AHR7372; Antezeyn Skowronek AHR5321; Azkar AHR1846; Abu Farwa AHR1960; GA’zi AHR5162; Rabiyas AHR1236.

Raad

AHR0474 1

Significant Down Line: Daareyn AHR1952

Rehal

AHR0504 3

Significant Down Line:

Lata AHR2289; Sheherzade AHR1081

Ribal

AHR0397 37

Significant Down Line:

Fadjur AHR7668; Fadi AHR16761; Fadjeyn AHR25142;Jureeka AHR13435; Khemosabi AHR45471.

Fersara AHR4104; Ferzon AHR7723; Gazon AHR9875; Raffon AHR19040;The Real McCoy AHR17362

Without listing all 272, we can quickly see several breeding programs that stand out from this group of Morabs. Aerohill, Box LT Ranch, Cross River, DAF, Jericho Creek, LJ, Liberty Mountain, RCF, SDR, Wayward, WRP, and Windmere. Without counting them, this group could easily represent more than half of the 272 and maybe one fifth of the1,000 or so Morabs registered in the International Morab Registry through 2004.

Many years later, there was a drive by

Arabian breeders to identify and record these original imports. The CMK

(Crabbet, Maynesboro, Kellogg) is a group of early United States top quality Arabians

identified by the founder of ‘CMK’ Dr. Michael Bowling. Dr Bowling provided much of my CMK material. The CMK sources include traditional English

breeding (Crabbet, GSB or Crabbet-Old English); horses imported or owned by W.R. Brown or

W. K. Kellogg; unique North American desert sources, such as (but not limited to) the

Hamidie, Davenport and Hearst imports; other individuals which were incorporated into the

Reese (Old California) and Dean (Midwest) breeding circles of the 1950's. These special

case individuals include, the Draper Spanish imports in California; *Azja IV and *Aeniza

in the Dean group. Its roots go back to

the Arabian desert through breeders in England, Poland, Egypt, France and Spain. CMK includes desert sources unique to itself like

the 1906 imports of Homer Davenport and the Hearst horses of 1947.

With the Crabbet, the Blunts and Lady Wentworth

influenced the direction taken by most of the Western Arab-breeding countries. Wilfrid and

Lady Anne Blunt began breeding Arabians at Crabbet Park in 1878 with desert bred’s

including Azrek and Rodania. To this very solid base they added such influences as Mesaoud

and Sobha, bred in Egypt from the stock of Abbas Pasha and Ali Pasha Sherif. Later the Blunts daughter Lady Wentworth

introduced a key outcross in the Polish Skowronek.

We know of William Randolph Hearsts’ great Morab

breeding program as detailed in the book, “Morab Moments”, but that’s

another story for another time.

©2005 Morab Publishing and the author.

Right to print given to Morab Perspective newsmagazine for

Spring 2005 issue.

Morab Historian Ted Luedke October 2000

CROSSBREEDING - A GENETIC DEAD END OR A

MASTERPIECE

or

PUREBREEDING – PROTECTING PREDICTABILITY

Crossbreeding or Purebreeding are the inventions of domestication and bound together as two distinct sides of the human quest to build a better horse. Nearly every breed group tussles with the definition of purity but to find true breed purity we need to go back some 100,000 years when nature did the selection, not man. Long before man started to domesticate anything, there was one subspecies of horse in Europe and as that species grew it developed traits to exist in that homeland. As it grew in numbers it moved out to the geographic limits of that homeland where those horse developed traits to exist in what was now their new homeland.

Territorial expansion and its adaptation gave rise to three more important subspecies – the oriental, the draft and the tarpan. Each had developed physical traits and characteristics for its own survival in its environment. It was during the next 2,000 years as man domesticated and bred what he wanted, that the groups stared to merge. The Arabian is still almost a 100 percent derivative of the oriental, but the Shetland pony would be the highest derivative, from the draft, isolated on the island of Britain. Pure, then, was based on geographic location. Scientists have shown that the Arabian horse has one less lumbar vertebra, two less in the tail, than other horses and they agree it is a true sub-species.

Fast forward into the 19th century and we find technology and transportation controlling and mixing the geographic pure gene pools. At some point man decided to keep records of breeding, partly to identify which matings produced the best offspring, but also to generate income from the business of record keeping.

Breeding like to like is very apt to produce more of the same. Predictability is the lifeblood of the closed book registry. Genetic uniformity drives from isolation and selection working hand in hand. Isolation can result from geographic restriction like the Icelandic Horses, or contrived like the mating of Arabians only to other Arabians.

TYPES OF REGISTRIES

OPEN – studbooks admit any horse, regardless of parentage, so long as set criteria are met. The most common characteristics are select performance skills and conformation, as determined by the founders of the registry, and color. Most of the European warmblood registries are open and if a horse has the qualities they think would improve the population, they admit them. Registration of offspring may or may not be acceptable, based solely on performance capability and not pedigree.

CLOSED – studbooks admit only the offspring of two registered parents, mostly with no particular restrictions on the animals’ physical/athletic characteristics. At some point someone decides that the horses already represented will create all following registrants. The Morgan registry (created by Battel when he listed some 400 horses in 1880) was an OPEN registry, allowing the registration of foals from the mating of a Registered Morgan to any other breed or grade horse. In 1948 they ‘closed’ to outside breeding and as time went on, the more genetically uniform the Morgan has become – hence predictability. Since Justin Morgan was not a pureblood to start with, and so many outcrosses have been made since, away from the original blood-lines, the Morgan cannot be referred to as a "pure-blooded" horse, although many of them have pedigrees back five or more generations in some branches of the family tree. The term was loosely used to represent those Morgans that had 4 or more generations of Morgan registered pedigree.

Breeding pure protects the distinct breeds as unique sources of repeatable and predictable combinations. Each breed has its intrinsic value, worth and uniqueness. We are wise to save homogeneous groups, for we really don’t want all horses to look and perform alike.

APPENDIX – studbooks (like The Morab Registry and the AQHA) are a hybrid of the Open/Closed studbooks that essentially sanction certain crossbreeding practices. The AQHA opened its books to offspring of AQHA registered horses mated to Thoroughbred by first passing through an Appendix, or directly through a set of performance standards. The Morab Registry allows the crossbreeding of Morgan and Arabian to produce first generation Morabs, and the breeding of Morabs to Morabs producing Fullbred Morabs.

It is ironic that people in the US get so caught up in "breed purity", because all the American breeds are just mixes of what people had around and liked. The appeal may be having papers documenting lineage and perhaps increased value. Crossbred registries like The Morab Registry do just that but also start the magic trail toward new consistency and predictability, starting as early as the second generation.

Crossing of distant types proves to be very useful in producing "just what the doctor ordered" in performance, as something greater that its parts. But this pairing of diverse and dissimilar genetic material (hybrid vigor) usually makes them poor bets for breeding on because the isolation and selection have not been working hand in hand over generations. This is where the Morab outdistances most of the other crossbreeds, in that it does not just use up genetic potential but rather contributes to it in such a way that subsequent generations continue to show the original cross characteristics and type. Second, third, fourth and even fifth generations have proved this without doubt.

HOW TO BUILD YOURS

The extended pedigree, data and knowledge of each and every

animal in the fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh generation may open the pages to

"skeletons in the closet" of which you little dreamed, and may enable you to

fortify your breeding program against glaring defects which would spring out to plague you

in offspring yet unborn. The Morab Registry can supply this detail going back

through the Arabian and Morgan pedigrees.

On the other hand you may find many "diamonds" in the extended pedigree, noted

animals which you did not know were ancestors of your horse. As you carefully work out

each generation you may find the same noted horse, or several of them, appearing again and

again in the pedigree as the common ancestor of horses in the more immediate pedigree, and

which you did not know were directly related. Thus you will be able to carefully weigh the

proportionate strength and weakness of the horses that appear two, three or more times in

the pedigree and get valuable, accurate insight into what the offspring will be like.

Pedigree is not a blueprint or a diagram of the individual but rather it defines the range

of possibilities within which the individual will fall.

Line-breeding and in-breeding are the old and time-proven methods by which breed improvement has been made in the past. All our present day breeds are the result of close line-breeding and often, intense in-breeding. There is no mystery where their finest horse came from. A study of their pedigrees will reveal that owners of pedigreed animals are well aware of the importance of line-breeding and in-breeding. However, you, too, with non-breed line mares may, by a definite breeding program and the proper selection of a stallion, employ the same methods of improvement in the foals.

In-breeding, since colonial years, has been believed to create deformed, small, weak as well as vicious, or deficient in brain capacity. It seems that the most commonly accepted fallacy among horsemen is that the practice of consanguinity or in-breeding in horses will immediately affect size and that small inferior "runts" will result, if they are not actually so grotesquely deformed that the foal dies shortly after birth. The study of pedigrees will show that the major breeds were primary users of in-breeding to obtain outstanding traits in the offspring. The trick is to remember that in-breeding features all the traits of the horses, both good and bad, so selection is the key to successful in-breeding.

The 1st goal of today’s Morab breeders is to combine the best traits of the Morgan and the Arabian to get that 1st generation outstanding crossbreed. Next is the goal to select from those 1st generation Morabs, those that will best reflect those traits in the first Fullbred Morabs. You will increase your chances if you:

Define exactly what niche the foal will fill,

Define what traits the foal needs to fit a niche,

Select sires & dams based on conformation, temperament and performance

Cull your breeding stock based on foals meeting your strict trait standards

Be patient

A FOOTNOTE: The Arabian horse, bred and raised for hundreds of years in desert country and on frugal if not actually scanty feed conditions responds immediately to good feed and care and the danger in this country is that the Arabian is growing a little bigger each generation and gradually loses its refined classic type and beauty. You need but look about you in your own family or the family of your friends to realize what better food, care and conditions have done for the human race in one or two generations in this country. It is not uncommon to see sons and daughters towering a head taller than their parents and it is commonly known that feet are universally larger in a single life-span.

Of the over 500 Morab breeders in the Morab Registry most are breeding 1st generation Crossbred Morabs. There are some active breeders that have over the past 10 to 15 years gone on to produce multiple generation Fullbred Morabs (Morab to Morab) including:

Windmere Farm

Jericho Creek Farms I & II

Magic Hill Farm

Box LT Ranch

Liberty MTN. Morabs

Mountain View Morabs

Breeding horses requires dedication and incredible patience – one foal per mare a year takes time!

Dr Michael Bowling November 2000

For Ted Luedke and used in MORAB PERSPECTIVE newsmagazine of the Morab Community Network

The Arabian breeding tradition now summarized in the phrase Crabbet - Maynesboro-Kellogg (CMK) was founded on the evaluation of horses on their individual merits; the CMK pedigree definition developed out of the study of the horses. CMK specializes in preservation breeding of the Arabian horse as established in North America before 1950, the most eclectic and freely-recombining gene pool in world Arabian history. Its roots go back to the Arabian Desert through the efforts of the original breeders of England, Poland, Egypt, France and Spain. As with many other subsets of the Arab-breeding tradition, CMK includes desert sources unique to itself. The most pervasive of these are the 1906 imports of Homer Davenport; a later-arriving set is the Hearst horses of 1947. CMK character has been shaped by the individual visions of its historical breeders; only the bare outline can be given here.

The Crabbet Arab stands with respect to modern Arabian horse breeding, as the Arab does to the light horse breeds; its influence is all-pervading. Genetically, through exports of horses, and philosophically, through the circulation of their ideas on type and breeding, the Blunts and Lady Wentworth influenced the direction taken by most of the Western Arab-breeding countries. No short treatment can do justice to the history of Crabbet and its horses, or to the three brilliant and complex characters who founded and developed it. Very briefly, as a result of their experience with the Arab horse on their desert journeys, Wilfrid and Lady Anne Blunt began breeding Arabians at Crabbet Park in 1878 with desertbreds including AZREK and RODANIA. To this very solid base they added such influences as MESAOUD and SOBHA, bred in Egypt from the stock of Abbas Pasha and Ali Pasha Sherif. In her turn the Blunts daughter Lady Wentworth introduced a key outcross in the Polish SKOWRONEK.

North American Arabian breeding also traces its beginnings back to 1878, for in that year the stallions *LEOPARD and *LINDEN TREE were presented by the Sultan of Turkey to former President Grant. These horses attracted the attention of a sophisticated trotting horse breeder, Randolph Huntington, who saw in them the opportunity to found a national horse for the United States. Huntingtons Americo-Arab project, based on the Grant stallions and mares by the trotting horse HENRY CLAY, was doomed to disappear. He did found a more lasting tradition when he imported the Old English (non-Crabbet) Arabian mare *NAOMI and sent her to *LEOPARD. The resulting foal of 1890, ANAZEH, was the first Arabian bred in North America to leave registered descent. Huntington imported three other Arabians from England, a daughter and two grandsons of *NAOMI.

In 1893 the Arabian horses of the Hamidie Hippodrome Society were sideshow exhibits at the Chicago Worlds Fair. Five of the Hamidie imports found their way into modern pedigrees, including *OBEYRAN whose daughter AARED founded the family to which BINT SAHARA belongs. Perhaps more importantly, they introduced the political cartoonist Homer Davenport to Arabian horses and led to his own desert journey and importation a few years later.

J.A.P. Ramsdell was an Arabian breeder for only a few years, but appears to have made an effort to collect the best stock available. His effective foundation mare was the best of the Hamidie mares, *NEJDME. Her descendants are prominent in modern pedigrees. Ramsdells sires were the Ali Pasha Sherif stallion *SHAHWAN, imported from Crabbet; *GARAVEEN, bought from Huntington; and Davenports famous Crabbet stallion *ABU ZEYD.

Spencer Bordens Interlachen Stud was the premier North American Arabian nursery of its day. Borden imported horses from the Blunts and from other English breeders; his most important individuals were the great mares *ROSE OF SHARON, a major producer at Crabbet and dam for Borden of *RODAN and ROSA RUGOSA; and *GHAZALA, bred by Ali Pasha Sherif, dam of GUEMURA and GULNARE. These are still accounted classical sources of quality in Arabian breeding.

Homer Davenport is responsible for the single largest contribution to the uniqueness of American Arabian breeding. At least 20 of his 27 desert imports have bred on into modern pedigrees. The Davenports represented an unusually broad cross section of the desert stock, for the tribes were in summer quarters at the time of his journey and he was able to contact more of them in the time available than could otherwise have been the case. *HAMRAH and *DEYR became the most influential of the Davenport sires, while there are too many healthy Davenport female lines to list; *WADDUDA and *URFAH are particularly influential.

W.R. Browns Maynesboro Stud was the successor to Bordens as the premier Crabbet nursery in North America, though in fact neither Brown nor Borden set out to breed straight Crabbet horses, or likely ever thought in such terms. At any rate the Crabbet and Old English heritage of the Borden, Ramsdell and Huntington stock would not be represented as strongly as it is in modern breeding were it not for Browns use of those lines at Maynesboro. The earlier Crabbet imports *RODAN, *ABU ZEYD and *ASTRALED were to leave their most influential descent through Maynesboro breeding. Browns own imports from Crabbet included the great sire *BERK and at least nine mares destined to found influential families. The publication of excerpts from the journals of Lady Anne Blunt throws an exciting light on the pedigrees of the Maynesboro imports. Wilfrid

Blunt, shortly after his wifes death, systematically sold off her most prized animals or their surviving offspring; many of the horses favorably referred to by Lady Anne in her journals are closely represented in Maynesboro pedigrees.

The Maynesboro Arabians represent the strongest surviving sources of many of the most esteemed early Crabbet lines, lines which in some cases are lost, or nearly so, from modern English breeding. GULASTRA, GHAZI, REHAL, RAHAS were just a few of the major sires bred at Maynesboro. The mare line founders include GHAZAWI, GHANIGAT, BAZRAH, RABIYAT, GHAZAYAT, RAAD, BAHREYN and NUSARA.

Maynesboro was not a farm where Arabians were kept in padded stalls. The horses were used for family riding and worked in light harness, and most visibly, took part in the U.S. Mounted Service Competitions, better known as the Army endurance rides. Both Borden and Brown had worked to get the Arab recognized as the natural horse for the U.S. Cavalry. Even though Browns horses retired the Mounted Service Cup by winning three of the Army rides, there were not enough Arabs to mount the Cavalry. The U.S. Remount did accept the Arab as worth standing to grade mares to breed potential cavalry mounts.

Brown also imported Arabians from France and Egypt. The Maynesboro French influence survives most strongly today through the mares FOLLYAT and FATH. The former is ancestress of MUHULI, AURAB and KONTIKI, while the latter produced ALYF and was granddam of the Selby matriarch WOENGRAN. The Brown Egyptians are still widely influential, including such familiar names as *NASR, *ZARIFE, *RODA, *AZIZA, and *HH MOHAMMED ALIS HAMIDA.

The next major nursery in North America was W.K. Kelloggs California stud at Pomona, diagonally across the continent from the New England beginnings outlined so far. Kellogg began with horses of Davenport breeding, and his stud played the same role in terms of that group as Browns did with the Borden, Huntington and Ramsdell stock. Much of the Davenport influence in modern Arabian breeding is there because the Kellogg management bought horses of this breeding, used some of them and placed others where they profited from the opportunity.

Crabbet Arabians were introduced almost immediately. Lady Wentworth was now at the helm and for financial reasons, horses were made available that might otherwise have been kept. The Kellogg importation of 1926 introduced the SKOWRONEK influence to North America, a fact which sometimes overshadows the other important Crabbet sources represented. *NASIK and *FERDIN were the other breeding stallions of this importation; the latter became a broodmare sire of note. The aged *NASIK, with few crops left to him, gave quality daughters, the top broodmare sires FARANA and SIKIN, and founded a distinguished male line especially through RIFNAS. *RASEYN by SKOWRONEK left 135 registered foals and became one of the most influential sires in the history of the breed, with FERSEYN and SUREYN his most noted sons. *FERDA, *RIFLA, *ROSSANA, BAHREYN and *RASIMA were chief mares of this group. Maynesboro horses also played a prominent role at the Kellogg establishment. The Brown mares referring not to color but to their breeder produced some of the best of the Kellogg stock.

RABIYAS, the last foal bred by W.R. Brown, was for years the Kellogg head sire, numbering among his offspring the horse probably most readily associated today with the Kellogg name the great ABU FARWA. Arabians from other sources, including the Draper Spanish import *NAKKLA and the Tahawia mare *MALOUMA, bred in Egypt from desert parents, became important members of the Kellogg program.

Once again, the Arab as the horse for cavalry was an important theme; in fact the Kellogg ranch and horses were donated to the Remount. For some years the program was run by the Army before it became part of Cal Poly Pomona, but by that time the Kellogg influence in Arabian breeding had extended far beyond the Pomona location.

Shortly after the Kellogg project began, Roger Selby started his own series of importations from Crabbet. The success of *RAFFLES makes it easy to overlook the desertbreds *MIRAGE; *SELMIAN, the only NASEEM son to come to this country; and the *NASIK grandson *MIRZAM. A number of Selby-imported mares founded major families, again including branches of lines which were lost in England. Selby also used Davenport mare lines, most extensively through WOENGRAN and AATIKA, though CHRALLAH produced two major *RAFFLES sons. The influence of the Selby Stud on Arabian breeding in North America has been profound, and any number of programs have been founded on the *RAFFLES or *RAFFLES-*MIRAGE influence in combination with assorted mare lines.

The last hurrah of the CMK founder programs came in 1947: Preston Dyer imported 14 Arabians from Lebanon and Syria for the publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst. Nearly all still are represented in pedigrees, though not as widely so as lines which had 50 years' head start. Hearst himself had owned Arabians for decades. His solid breeding program was founded on Kellogg and Maynesboro stock; the 1947 stallions such as *MOUNWER, *GHAMIL and *ZAMAL bred on particularly well, and most of the mares founded families.

Within the CMK tradition, individual breeders may emphasize different sources of the old stock, and make use of additional Blunt samples provided by more recent English or Australian imports. Ingredient names such as Crabbet or Davenport are used in two different senses in talking about modern stock; these foundation animals are spread throughout the breed and highly valued in CMK circles; a subset of their influence is prized in the form of modern straight breeding.

Latterly CMK has emphasized maintaining direct inheritance from the old founder sire and dam lines. The constant theme is that of selection toward an ideal combining Arabian character with riding conformation, performance ability and a mental outlook which accepts training. This is the kind of Arabian the Blunts and Davenport brought home from the desert, the kind that won the Army rides for Brown, the kind that can still be competitive in todays complex Arabian scene.

NOTE:

An email from Dr Bowling giving further detail on a specific group of Arabian enthusiasts

that struggled with early heritage before the CMK was founded follows:

Date: Mon, 13 Nov 2000 10:38:03 -0800

From: michael bowling <cmk@davis.com>

Subject: Re: The *Nasik Group

Well--we are talking every bit of 30 years ago, so it may well be that I have lost track of some details of the chronology (and quite possibly ofwhole aspects of the story). The *Nasik Group never "happened"--it was never made public; some people who took part in the discussions and the development of the concepts actively dissociated themselves from the name.

But it served as the arena for some of the original discussions out of which the CMK concept would evolve.

Even at that stage, and even though we could not have put it into words at the time, we were seeing in embryo the dichotomy between "preservation" and "promotion" that still causes occasional misunderstandings. We had people( this was just a handful of us) who wanted no reference to pedigrees at all, just strictly to organize group advertising with which anyone could join. We had one or two others who actually were thinking in terms of a minimum pedigree percentage of *Nasik ancestry.

Oddly enough I still have a copy of the little manifesto that I wrote, after some correspondence had gone on about this subject. I am virtually certain it was done on the typewriter I used when I was in grad school, and if so it must have been completed by mid-1972 at latest.

Viz:

"The *Nasik Group is an unstructured association founded primarily for the

preservation of Arabians of the quality we associate with the Maynesboro Stud of W.R.

Brown and the Pomona Stud of W.K. Kellogg.(later the U.S. Remount). Secondary

purposes include promulgation of higher standards of ability, conformation, type and

Arabian character than we see reflected in most contemporary breeding programs and show

results. Third in importance is the promotion of *Nask Group Arabians.

"The Crabbet stallion *NASIK has been chosen as the symbol of this effort partly because he is one of the greates of the forgotten Arabians whose influence has come to be ignored in favor of later fashiones, but largely because he combined, as an individual and as a breeding force, so much of the excellence we seek in these horses. We cherish particularly the dcescendants of *Nasik and of several of his close relatives, and of certain of his approximate contemporaries whose lines have proven to blend well with his.

"We seek to salvage the genes of these hroses where we can come by them; we value the study of pedigrees as an aid to selection, but not as a substitute for it. We expect the majority of horses meeting our standards of individuality and production to be derived predominantly from Crabbet-Maynesboro-Kellogg breeding, but we also prize certain horses of other breeding backgroundsm abd are not interested in a purely pedigree elitisim."

I did remember that this was written before we recognized that it was not possible to draw a line between the Selby horses and other aspects of this breeding tradition, but I had honestly forgotten that it explicitly included the words "preservation" and "Crabbet-Maynesboro-Kellogg"--it is interesting and informative to revisit past history, from time to time. Dr Bowling

Questioning Breeding Myths

In Light of Genetics

Ann T. Bowling PhD for Ted Luedke ©1995

"Breeders cannot change Mendelian genetics, nor

the number of genes involved in traits, nor their linkage relationships. They cannot

change the physiological interactions of gene products, but they can hope through

selective mating to realize gene combinations that consistently result in high quality

stock."

Newcomers to horse breeding

often look for pedigree formulas or hope

to emulate a particular breeder's program by using related stock. Unfortunately for

novices, the truths of horse breeding are that many successful horse breeding judgments

are in equal measure luck and intuition. Horse breeding is not as easy to fit to formulas

as breeding for meat or milk production. Many of the highly valued traits of horses such

as breed type or way-of-going are subjectively evaluated in show ring events. Winners may

reflect the skills and show ring savvy of the trainer/handler, as much as the innate

abilities of the horse. Some breeders can learn to predict to their satisfaction the

approximate phenotype to expect from a selected mating because of their years of

experience studying horses and their pedigrees, but their skill cannot always be taught to

others and may not work with unfamiliar pedigrees.

Nicks

Horses

considered to be of excellent quality often present

a pattern of recurring pedigree elements. Breeders naturally seek to define pedigree

formulas or "nicks" to design matings that will consistently replicate this

quality. But breeding horses is not like following a recipe to make a cake. You cannot

precisely measure or direct the ingredients (genes) of the pedigree mixture as you can the

flour, sugar, chocolate, eggs and baking powder for a cake. You can construct pedigrees to

look very similar on paper, but the individuals described by those pedigrees may be

phenotypically (and genetically) quite different. Before seriously considering any

breeding formula scheme it is essential that breeders understand the most basic lesson of

genetics: each mating will produce a genetically different individual with a new

combination of genes.

A

certain nick is often expressed as cross of

stallion A with stallion B -- an obvious impossibility! Probably one source of this

convention is that it is easier to become familiar with the characteristics of the

offspring of stallions than mares because they usually have a greater number of foals.

Another source is the perceived need to reduce complex pedigrees to an easily described

summary. Breeding stallion A to daughters of stallion B (this would be the genetically

correct description of some nick) may produce horses of a relatively consistent type

compared with the rest of the breed. For mares of the next generation, the

"magic" nick (stallion C) is again at the mercy of genetic mechanisms that

assure genes are constantly reassorted with every individual and every generation. Some

breeders are reluctant to introduce stallion C at all, preferring to continue with their

A-B horses, breeding their A-B mares to A-B stallions. If a nick works, and it can appear

to do so for some breeders, basic understanding of genetics tells us that it is seldom a

long term, multi-generational proposition unless it is guided by an astute breeder that is

making breeding decisions on individual characteristics, not merely the paper pedigrees.

Basing a program on champions

Novice

breeders are often counseled to "start with ia

good mare." This seems to be reasonable advice, but does not make it clear that the

critical point is to learn to recognize a good mare. Sometimes breeders fail to produce a

foal that matches the quality of its excellent dam, while less impressive mares in other

programs produce successfully. Probably the lack of objective criteria to evaluate horses

accounts for both observations. A "good mare" need not be a champion, and a

champion is not guaranteed by dint of show ribbons to be a "good mare." As well,

we do not know the inheritance patterns of highly valued traits for show ring excellence.

If the ideal type is generated by heterozygosity (for example, the ever useful example of

palomino), the only infallible way to produce foals that meet the criterion of excellence

(palomino color) is to use parents of less desirable type (chestnuts bred to cremellos).

This example is not to be taken as a general license to use horses of inferior quality,

but to provoke critical thinking about the adequacy of general breeding formulas to guide

specific programs.

Other breeders pride themselves in structuring programs based on using exceptional stallions. However, breeders should be aware of the fallacy of this type of strategy: "I like stallion Y but I can't afford the risk to breed my mare to an unknown stallion like Y -- I can only breed to a National Champion like Z." Any breeding is at risk to produce a less than perfect foal, but the advertising hyperbole leads novices to think that certain avenues are practically foolproof. Included in the best thought out breeding plans must be an appreciation of the ever-present potential of deleterious genes being included with those highly prized. It is irresponsible to assume that an animal is without undesirable genes. The wise breeder understands the task as minimizing the risk of creating a foal with serious defects and maximizing the chances of producing an example of excellence.

A master breeder needs several generations (generation interval of horses is estimated to be 9-11 years) to create a pool of stock that contains the genetic elements that he or she considers important for the program vision. To learn to identify essential characteristics, a breeder needs to evaluate the horses and their pedigrees, not advertisements or pictures. When a breeder discovers those elements, he or she can make empirical judgments and is on obvious path for making good breeding decisions.

The

cult of the dominant sire

In

some circles, the highest praise of a breeding

stallion is that he is a dominant sire. Another widely encountered livestock breeding term

for an elite sire is prepotency. The implication is that all his foals are stamped with

his likeness, regardless of what mare is used. This concept would appear to contradict the

advice "start with a good mare." Those owners who strongly believe in the

strengths and qualities of their breeding females would surely question the value of a

so-called dominant sire who could seemingly obliterate valued characteristics that would

be contributed by their mares. A good understanding of genetics should allow a breeder to

put the proper frame of reference to terms such as dominance and prepotency as applied to

breeding horses. Some animals transmit certain characteristics at a higher frequency than

is generally encountered with other breeding animals. Coat color is always the conspicuous

example. Any stallion whose offspring always or nearly always match his color is popularly

described as a dominant sire. To be excruciatingly correct, for at least some of the

effects being considered the genetic interaction is not dominance but epistasis and

homozygosity. A stallion could be homozygous for gray, leopard spotting or tobiano, so

that every foal, regardless of the color of the mare (with the possible exception of

white), would have those traits. Homozygosity for color is not necessarily linked with

transmission of genes for good hoof structure, bone alignment in front legs, shoulder

angulation or other traits that may be desirable. Most conformation traits seem to be

influenced by more than one gene. Some stallions may be exceptionally consistent sires of

good conformational qualities, but it is unlikely that every foal will have these traits

or that any stallion could be so characterized for more than a few traits. The balanced

view is that a battery of stallions is needed to meet the particular genetic requirements

of each of the various mares in the breed. No one stallion can be the perfect sire for

every mare's foal.

Using genetics to guide a program

If assays for genes important for program goals are available,

the probability of obtaining foals with selected traits from specific breeding pairs can

be predicted. For many horse coat colors, offspring colors can be predicted, but

conformation and performance traits are not well enough defined for predictive values to

be assigned. So little is known about the genetics of desirable traits, it is premature to

suggest that any general technique of structuring pedigrees consistently produces either

better or worse stock.

The important lessons to learn from genetics to use for horse

breeding decisions may seem nebulous to those looking for easy "how-to"

information. Yet an appreciation of how genes are inherited, the number of genes involved

in the makeup of a horse, their variability within a breed and the inevitability of

genetic trait reassortment with every individual in every generation will provide the

critical foundation for sound breeding decisions.

With the current interest

in genetics and the new technologies

available for looking at genes at the molecular level, information about inherited traits

of horses is likely to increase significantly in the next decade. Horse owners can help

with the process in several ways, including communication with granting agencies about

specific problems of interest to them, providing money to fund the research, and providing

information and tissue samples to funded research studies. Horse breeders are eager to

have sound genetic information and diagnostic tests to guide their programs and

fortunately, the future looks very promising.

First Copyright 2004; All rights

reserved by Box LT Publishing

Created : 1/28/2004. Update : 9/31/2006

Ranch Info Photo Tour Sales Stallions Mares Foal Scrapbook Pinto

Publishing Fainting Goats Katy Kreations

Favorite Links

Ozark Mountain Station

Marines

Speak Out

Leave the site for these Marine

sites (but come back please):

Marine Corps League National

MCL Springfield, MO